What can we make of the past? I mean that literally here – what from the past can we carry forward and transform into an object relevant to the present? This question often comes to mind when I’m looking at old furniture in a museum.

Sure, it’s important to take objects on their own terms, but sometimes I can’t resist wondering if the design of a 1790s sideboard could be tweaked a little to fit a stereo. “But can you put a TV in there?” How many designers earned their keep by answering that question when looking at early American case furniture in the decades before flat screens? I recently completed a piece that begs these kinds of questions. It’s a complex writing table copied directly from a mid-18th century English original at Colonial Williamsburg (CWF 1980-152). In period terms, we might call this a writing table with a double rising top and writing drawer. In other words, you can sit at it or stand, use it comfortably alone or with another, and easily move it around a room and then close it all up into an unassuming little table that stays out of the way. It was perfect for the quill-pen-wielding gentleman of long ago, but can this transforming table be transformed into something useful for today’s world? Let’s take a close look at this table and start asking some questions.

Writing tables like this are less familiar today than in the past. What is very familiar however, is the concept of a standing desk. “A standing desk – even back then?! That’s so trendy now!” That was a common refrain among visitors to the Hay Shop in Colonial Williamsburg while I was building and discussing this piece. Plenty of standing desks with fixed or adjustable tops were made in the 1700s, and though they used different words to describe it, the makers understood the importance of ergonomics. Sometimes old ideas seem new. The ability to adjust the height and angle of the main writing surface hinges on two styles of mechanisms, but no complex modern hardware. First, for adjusting the angle of the top and the drawer’s writing surface we have the ratcheting mechanism that some period writers called a horse.

This has always been a great, low-tech solution to adjusting angles and supporting surfaces with a respectable strength. There’s also a deeply satisfying clickety-clack as the horse skips across the teeth while you raise a surface. On the downside, those teeth are prone to chipping, and it is a challenge to line up the hinges and both sides of the horse with the teeth that support it. There are plenty of techniques for getting everything right, but that’s a story for another time. The horse is still quite useful for today’s designer. I’m planning on incorporating a robust version in a carver’s bench I’ll be making for myself.

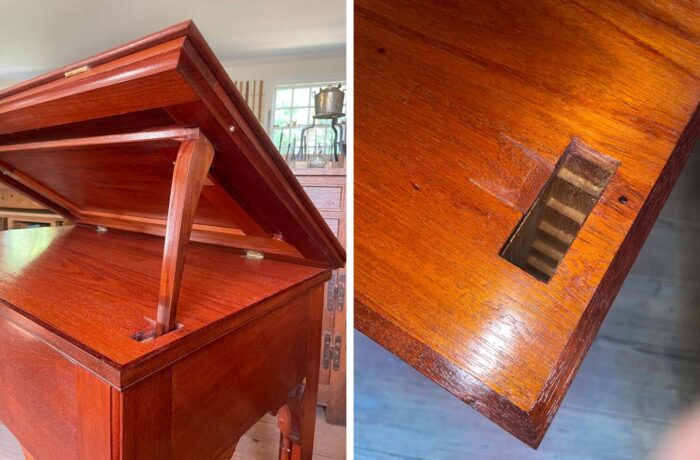

I don’t know what past makers called the slender saber-shaped supports that dive down into the table’s legs – I call them sabers or tusks. Regardless, these feel a little too thin to me, but the idea works nicely in general. It’s like the horse where the end of the saber locks into a nearly vertical version of the teeth that steps down into the leg like a little staircase (image on right). To keep the whole thing moving together, the two sabers are joined together by a bar at top. Hiding the adjustment in the leg requires some cleverness in design and makes repair difficult, but it does offer a clean finished appearance.

Certainly, all these adjustments are still useful as is, but as we type more and write less, do they still have a place, and where? One thing is for certain, the table’s ability to explode up and out and then compact and retreat into a room is still useful. For the 18th-century gentlemen with multi-use rooms, it was a convenience. For the person working from home on a laptop all day in a small house or apartment, maybe a variation of this design is what keeps the work-life balance in order. When the workday is over, throw the laptop in the drawer, close it, and forget about those emails until tomorrow.

Out comes the drawer

The writing surface on the drawer is called a slider because, you guessed it, it slides back to allow access to the drawer box. That green broadcloth looks nice, but it is there to help the ink flow nicely from a quill. Do you write like that? I would keep the slider, but replace its adjustable writing surface with a fixed board that provides a stable base for my laptop or tablet that could then be stored below when not in use. The flip-out quadrant drawer (at right in above photo) remains a handy place to store pens and the like without having to move anything out of the way.

This drawer is practically a piece of furniture itself with two legs and three drawers of its own. In addition to the quadrant drawer, there are two secret drawers hidden below the interior partitions as pictured above. We may protect many of our secrets with passwords these days, but an actual secret drawer is always a welcome feature and a great way to practice your tiny dovetails.

Finally, let’s consider drawers with legs. This is undeniably a great way to support a heavy drawer that doubles as a work surface of any kind. That structural advantage has some downsides, though. Most significantly, the long, narrow legs don’t have any support down low, so they are prone to distortion over time. This problem becomes noticeable when the drawer’s legs fail to align properly with the table’s front leg when closed. To conceal this eventual problem, the original makers planed a simple molding down the length of the drawer leg. When the drawer is closed, this nestles into the table leg whose narrow leading edge acts as a fillet that completes the molding and creates an intentional shadow that helps conceal any gap between the two legs. Like making a drawer with legs, this is a clever solution that we can apply to any number of circumstances. How can you use variations of these techniques in your own work? The past has left us a lot of ideas to borrow and reimagine.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.